How Wildlife Traffickers Use Chinese New Year

Feb 08, 2019

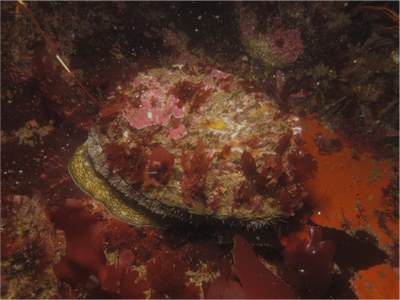

The animal is a popular ingredient in Cantonese cuisine, particularly for celebrations. Individuals caught in the wild fetch a higher price than those farmed in China. Those from South Africa, where abalone used to be abundant, are especially popular.

When commercial trading to China started in the 1990s, abalone numbers quickly dwindled, leading the South African government to impose quotas. That only served to move the trade underground. In the past 18 years, a staggering 96 million abalone were caught in South Africa, worth a total of nearly US$900 million. More than 90% of those were exported to Hong Kong, with considerable numbers then moved on to mainland China, according to NGO Traffic.

“Serving something expensive at Chinese New Year can show your status to the people around you,” says Traffic’s Michelle Owen, who leads the USAID Reducing Opportunities for Unlawful Transport of Endangered Species (ROUTES) Partnership.

Traffic estimates that more than 30% of people in Hong Kong consume the pricey delicacy during the festival. Processors say to meet demand they have to double production ahead of Chinese New Year.

Unwitting families feasting on South African abalone during their New Year celebrations are more likely to be supporting organised crime than not. In Hong Kong, only around 35% of South African abalone was farmed or caught legally.

Traffic in the post

In their covert operations, wildlife traffickers are increasingly relying on the same transport routes and means that any of us use to send mail or travel home.

The shipping industry and parcel couriers are overburdened in the weeks leading up to Chinese New Year. Customs officials are stretched so thinly that the ratio of inspections drops. That’s why illicit goods are more likely to get through.

“In plane sight”, a report published by ROUTES in 2018, tracked seizures of trafficked wildlife in cargo and passenger planes and found that they more than quadrupled between 2009 and 2017.

“The transport industry has very good infrastructure, and traffickers have been exploiting this to their benefit,” Owen says.

This can include bribing customs officials, exploiting their shift patterns, knowing which locations are less stringent on controls, or when an increased flow of traffic will make it impossible for customs to keep up with controls.

Holiday smuggling

Chinese New Year and other festivals that see an increase in shipping and air travel provide good cover for wildlife traffickers.

Between February 4-8, Hong Kong customs and police forces are expected to handle a staggering 7.32 million people crossing its borders by land, sea or air. The Civil Aviation Administration of China said that between January 21 and March 1, it will help handle 73 million passenger trips by air, an increase of 12% on the previous year. This mass of travellers makes it harder for customs to check passengers and their luggage.

Similarly, shipping increases ahead of Chinese New Year as importers preemptively make up for the one- to two-week standstill in work and production over the national holiday.

Even in non-festive periods, customs stations are struggling to keep up with the rapidly growing international shipping and parcel delivery industry.

According to DHL, the world’s largest international delivery service, worldwide cross-border retail has been growing by an average of 25% per year – twice that of domestic retail. In China, the express delivery sector has been handling 10 billion more parcels each year since 2015, according to the State Post Bureau.

While cargo fleets are growing by around 4% per year, and volumes grow by between 4 and 4.5% globally, these rates are much higher for most of East Asia. The port of Shanghai, for instance, saw a growth of 142% over a ten-year period from 2007.

A global problem

China is the biggest market for trafficked wildlife but it is not the only one. Customs and law enforcement agencies in 136 countries recorded around 7,000 different species in wildlife trafficking seizures between 2009 and 2017, ranging from elephant tusks and pangolin scales to live lizards and rare dog breeds, according to the UN.

Smaller shipments sent through delivery services are growing.

“If you see what’s going on in the international parcel industry today, and how it has grown, it’s just enormous,” says Harold Gerretsen, an inspector with the Nederlandse Voedsel-en Warenautoriteit, the Dutch food and consumer product safety authority. It’s responsible for detecting violations of CITES, the international treaty to protect endangered species, and works closely with Dutch customs at points of entry such as Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport and the port of Rotterdam. Both were highlighted as prime wildlife trafficking locations by the EU, which acknowledged in 2016 that it “has an important role to play in tackling this traffic”.

Gerretsen says that although containers full of trafficked wildlife continue to be intercepted, big hauls are becoming rarer. Instead, smaller shipments sent through delivery services are growing.

“The best way to smuggle is to go with the flow, wherever the stream is biggest,” he says. “If you have millions of parcels every year, how much can you possibly inspect?” he says.

In Europe and other Western countries, customs officers are stretched during Christmas, the busiest time of the year for mail and parcel services.

In the weeks leading up to and right after the holiday, parcels and mail passing through major airports more than double. To handle the massive spike in deliveries, Deutsche Post, for instance, said that it would hire 10,000 seasonal workers in 2018, mostly for low-skill tasks such as parcel sorting and delivery driving.

But hiring seasonal help isn’t an option for customs authorities. Officials need at least two years of training, including in local and international law, and rely on their experience to know which shipments are suspicious, said a press spokesperson for customs in the German city of Frankfurt, one of the world’s busiest airports.

At Frankfurt airport’s International Postal Centre, about 90 customs officials inspect 10,000 to 12,000 parcels a day on average, one of the officials, Marcus Redanz, estimated. In 2017, his team seized 5,500 shipments that contained trafficked animals and plants. They had come from all parts of the world and included ivory, the pelts of bears, mountain lions and polar foxes, and wallets and handbags made from crocodiles. These animal products are now stored in a fenced-off area of the postal centre.

Keeping up with the traffickers

How quickly professional traffickers can adapt is evident in the South African abalone trade. In 2007 and 2008, smugglers started to explore alternative trafficking routes to avoid the government’s new regulations and stricter controls on imports into Hong Kong. It’s now believed that smugglers are taking abalone first to neighbouring countries like Mozambique and Zimbabwe, before then exporting.

In September, for instance, South African police found 10 kilogrammes of illegally poached abalone on a truck headed to Botswana. News reports claimed the abalone was worth US$400,000. According to Traffic, 90% of South African abalone is exported to Hong Kong.

The challenge, says Owen, is staying a step ahead of the traffickers but she acknowledges that customs are often busy with bigger threats to national security.

If staff at airports, flight attendants and luggage handlers could be customs’ additional eyes and ears, more wildlife could be seized – no matter the time of year.

“They do the check-in, they talk to passengers, they handle their bags. It’s important to build their awareness of what to look for in someone who might be trafficking wildlife and who they can contact to make their suspicion known,” Owen says.

Currently, ROUTES is working with airlines and the delivery industry to find ways to help overburdened customs officials, including by offering short training modules for staff.

The fact that traffickers are using the same routes as mail or passengers “can actually be a big opportunity,” says Owen.

Denise Hruby is a journalist based in Vienna, Austria, who covers social and environmental issues and conflict across the world, from Southeast Asia and China to Europe and East Africa.

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network. This article appears courtesy of China Dialogue Ocean, and it may be found in its original form here.